The government of Canada website provides an overview of the national and international framework for human rights treaties, stating that:

Canada has been a strong voice for the protection of human rights and the advancement of democratic values, from our central role in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1947–1948 to our work at the UN today. Canada has ratified seven major UN human rights treaties and must submit periodic reports on how it implements each of these treaties.

The government further acknowledges that: “Canada plays a major role in promoting universal respect for human rights on the international stage. While we provide support abroad, we must also account for our actions within our country to identify strengths and areas where improvements are needed.”

According to both domestic and international opinion, one area where improvements are needed in Canada is child rights.

The treaty governing compliance on these rights is the United Nations – Convention on the Rights of the Child – UNCRC, and the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, which oversees compliance, has noted fundamental problems with Canada’s record and reporting on child rights since the first round of review after Parliament ratified the treaty in 1991. The gap created by a federal-provincial jurisdictional split arises as a repeated and major concern in these early discussions, such as this exchange between Committee member Mrs Santos Pais and Mr McAlister from the Canadian delegation:

CRC/C/SR.214 – 30 May 1995. CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS OF STATES PARTIES (continued)

46. Mrs. SANTOS PAIS said that she had two main comments to make regarding the replies of the Canadian delegation. First, while regional differences between different provinces and territories must be taken into account during the ratification process, the Federal Government was committed, once the Convention had been ratified, to enforcing the Convention’s provisions throughout Canada, and was responsible for reporting to the Committee on implementation. Under article 4, States parties were obliged to adopt all appropriate legislative, administrative and other measures required to implement the Convention, and the Committee needed to know what mechanisms existed to ensure such implementation. While it was true that various human rights charters had existed in Canada before the Convention had been ratified, the Convention to some extent marked a new departure or new “common denominator”. What mechanisms existed to ensure that real progress was being made in implementing it? How were data on implementation collected? Were there adequate means of overcoming existing disparities among different population groups and giving particular help to the most vulnerable groups?

47. Mr. McALISTER (Canada) suggested that attention needed to be focused primarily on whether Canada was fulfilling its obligations under the Convention, rather than on the ways and means by which it did so. While Canada was quite prepared to provide more information on, for example, coordination between the federal and provincial governments, the Committee would do well not to lose sight of the actual situation with regard to the rights of children in Canada which was very favourable. The federal system of government was a complex one which had developed over many decades, and under which the provinces had exclusive rights in certain areas of jurisdiction. Nevertheless, the commitment to human rights and, in particular, to the rights of children was universal throughout the country, a fact attested by the existence of various commissions and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and the overall level of protection for those rights was excellent.

Despite this reassurance, the concluding observations of the Committee, published a few weeks later, state that jurisdictional gaps in protection of child rights in Canada continue to be a ‘principal subject of concern’:

CRC/C/15/Add.37 – 20 June 1995 – COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD, Ninth session, CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 44 OF THE CONVENTION. Concluding observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child: Canada

C. Principal subjects of concern

9. The Committee, while taking note of the statement, reflected in the report of the State party, that the federal nature of Canada is a complicating factor in the implementation of the Convention, and that the exact division of responsibilities between federal, provincial and territorial governments over matters affecting children may involve an element of uncertainty, stresses that Canada is bound to observe fully the obligations assumed by ratifying the Convention. The Committee is concerned that sufficient attention has not been paid to the establishment of a permanent monitoring mechanism that will enable an effective system of implementation of the Convention in all parts of the country. Disparities between provincial or territorial legislation and practices which affect the implementation of the Convention are a matter of concern to the Committee. It seems, for instance, that the definition of the legal status of the children born out of wedlock being a matter of provincial responsibility may lead to different levels of legal protection of such children in various parts of the country.

This disparity ‘between provincial or territorial legislation and practices’ remains more than 20 years later, although a remedy for the problem of divided jurisdictions and responsibilities for child rights in Canada was suggested long before the UNCRC was ratified in 1991.

A member of the Canadian Commission for the International Year of the Child, rights activist and former Senator Landon Pearson (founder of the Centre for the Study of Childhood and Childrens’ Rights), first proposed in 1979 that the children of Canada should have their own advocate; an appointed person and an office that operate with national scope to deal with matters of child interest in all regions and jurisdictions of the country. The advocate would have comprehensive scope to speak on behalf of children in Canada, bridging gaps and ensuring that each and every child receives protection and the benefit of their rights under international treaty requirements.

The call for a National Advocate for Children in Canada has been endorsed and repeated many times since 1979 – by Landon Pearson and by other voices – with a recommendation for a National Strategy for Children. But there has been no action from the succession of Canadian governments responsible for making a decision on this matter since then or in the 26 years since ratification of the Convention.

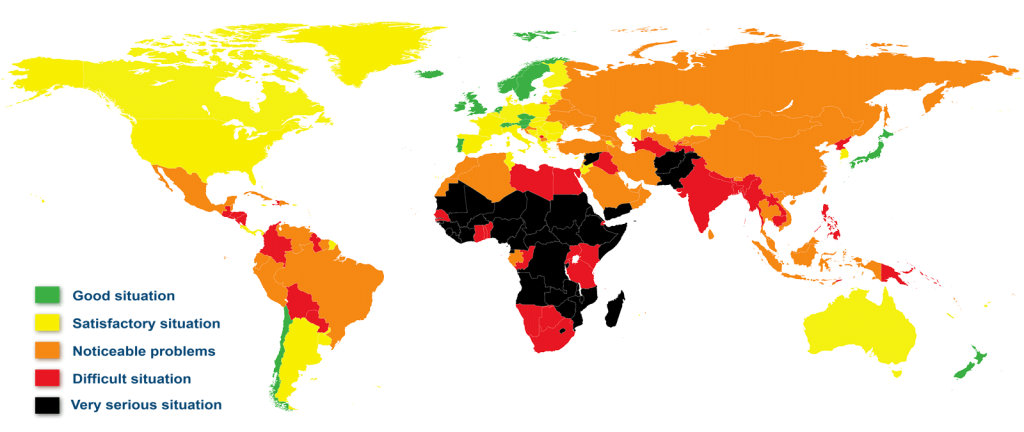

Meanwhile other state parties have successfully adopted and implemented their own national child strategy. So while Canada still operates at the national level with an association of regional child advocates (Canadian Council of Child and Youth Advocates – CCCYA), the EU has an international coalition of state party advocates (European Network of Ombudspersons for Children – ENOC), coordinating laws, services, and actions in the interests of children arriving and living across diverse jurisdictions.

The next report for Canada to the UN-Committee on the Rights of the Child, due in July 2018, is an opportunity to fill this long-standing and widely recognized national gap for child rights protection. As part of its submission, Canada can commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by appointing a National Advocate for Children and creating an office that is mandated to fulfill international human rights treaty obligations to children under the UNCRC.

This office will also move Canada into the position anticipated by its published claims as a state party that lives up to and leads on human rights commitments, and will provide credentials for an expanded role in global actions.